Signs and symptoms of LC-FAOD

LC-FAOD CAN AFFECT MULTIPLE ORGANS AND TISSUES

Signs and symptoms of LC-FAOD typically manifest in tissues that rely on energy production via fatty acid oxidation, such as the liver, heart, and skeletal muscle.5

Patients may not experience all of these signs and symptoms, and they may experience them at different times.5-8

- Developmental delay

- Peripheral neuropathy

- Irreversible nature poses lifelong impacts

- Hypoglycemia

- Hepatic dysfunction

- Chronic liver dysfunction

- Nausea

- Gastrointestinal distress

- Lack of appetite

- Rhabdomyolsis

- Muscle weakness (hypotonia)

- Muscle pain (myalgia)

- Exercise intolerance/avoidance (may lead to sedentary lifestyle; increased risk of obesity)

- Progressive retinal dysfunction

- Decreases in color, low light, and central vision

- Cardiomyopathy

- Pericardial effusion

- Heart failure

- Arrhythmia

- Sudden death

Adapted from Merritt JL, et al. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2020;21:479-493.

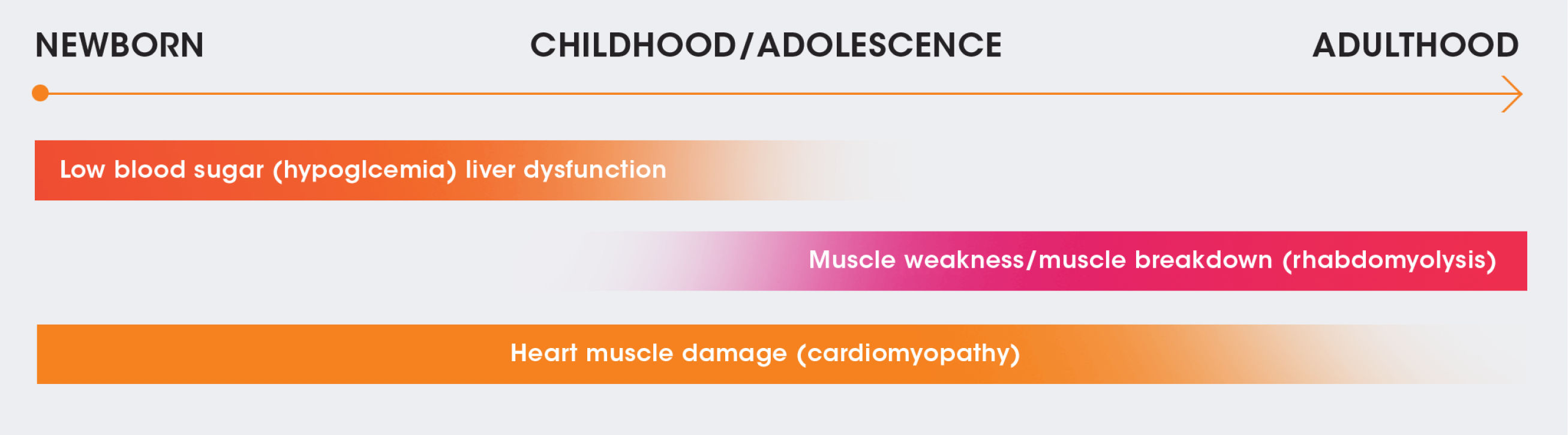

A SPECTRUM OF PRESENTATION

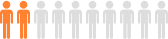

Although symptoms can appear within a few hours of birth, they may also not appear until adulthood. They can evolve over time and may differ depending on when they appear.5,7,8

Onset of symptoms in asymptomatic patients can be rapid and unpredictable. Patients should therefore still be monitored closely.6,9

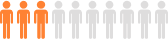

NEWBORN

CHILDHOOD/

ADOLESCENCE

ADULTHOOD

Low blood sugar (hypoglycemia)/liver dysfunction

Muscle weakness/muscle breakdown (rhabdomyolysis)

Heart muscle damage (cardiomyopathy)

CHRONIC SYMPTOMS AND ACUTE EPISODES

Many patients with LC-FAOD experience lifestyle limitations, as well as significant morbidities and life-threatening complications, such as1-3:

Chronic symptoms of fatigue, muscle pain, and weakness5

- Arise or are exacerbated during catabolic situations, such as fasting, illness, and endurance exercise1,5,10

- Are chronic and progressive manifestations resulting from prolonged energy deficiency and tissue/vital organs fatty acid accumulation1,3,10

Acute episodes that often involve rhabdomyolysis, cardiomyopathy, or hypoketotic hypoglycemia1,5

- Are usually triggered by illness or fasting, but they may occur spontaneously and unpredictably in some LC-FAOD types, with long-lasting implications1,5,10

- May lead to hospitalization, emergency room visits, emergency treatment interventions, and sudden death1,3,11

Despite early detection and management, LC-FAOD mortality rates tend to remain high.3

DIMINISHED HEALTH-RELATED QUALITY OF LIFE

Patients with LC-FAOD experience substantially diminished health-related quality of life, with negative impacts on physical, mental/emotional, and social functioning.3,12

Constant supervision

Patient care may require a round-the-clock commitment, including supervision of diet and nutrition, monitoring of energy levels, and watching for signs and symptoms of decompensation and/or fatigue.9,11,13

Emotional well-being

Uncertainty and fear surrounding the condition and long-term impact of disease can have a detrimental effect on emotional well-being.4

Anxiety and depression

In a study intended to determine health-related quality of life among patients with LC-FAOD and their caregivers, preliminary results showed increased anxiety among parent caregivers.4

Avoidance of triggers

Continual avoidance of triggers such as exercise, viral illnesses, and cold or hot weather, and the risk of recurrence may lead to anxiety and depression.4

A 2022 survey of 51 LC-FAOD patients revealed:14

Hospitalizations had a significant impact on LC-FAOD patients and caregivers14

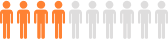

Patients

59%

84%

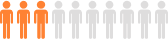

Caregivers

70%

“Hospitalizations” was the primary reason given in each case

Effects on schooling included reduction in study load and staying home/attending fewer days per week

Effects on work included changing jobs, stopping working, reducing work hours, and turning down job opportunities

Adapted from Kruger, 2022.

Patients had difficulty doing basic things such as:14

Standing/being on feet for two hours (20/47)

Lifting/carrying up to 10 lb (13/45)

Walking 400 m (16/49)

Doing chores around the house (10/45)

Pushing/pulling large objects (14/44)

Adapted from Kruger, 2022.

References

1.Saudubray JM, Martin D, de Lonlay P, et al. J Inherit Metab Dis. 1999;22(4):488-502. 2. Shekhawat PS, Matern D, Strauss AW. Pediatr Res. 2005;57(5 Pt 2):78R-86R. 3.Vockley J, Burton B, Berry GT, et al. Mol Genet Metab. 2017;120(4):370-377. 4.Siddiq S, Wilson BJ, Graham ID, et al. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2016;11(1):168. 5. Knottnerus SJG, Bleeker JC, Wüst RCI, et al. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2018;19(1):93-106. 6.Merritt JL 2nd, MacLeod E, Jurecka A, Hainline B. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2020;21(4):479-493. 7.Vockley J, Marsden D, McCracken E, et al. Mol Genet Metab. 2015;116(1-2):53-60. 8.Spiekerkoetter U. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2010;33(5):527-532. 9. Merritt JL 2nd, Norris M, Kanungo S. Ann Transl Med. 2018;6(24):473. 10. Wajner M, Amaral AU. Biosci Rep. 2015;36(1):e00281. 11. Vockley J, Burton B, Berry GT, et al. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2019;42(1):169-177. 12. Yamada K, Shiraishi H, Oki E, et al. Mol Genet Metab Rep. 2018;15:55-63. 13. Evans S, Shelton F, Holden C, Daly A, Hopkins V, MacDonald A. Arch Dis Child. 2010;95(9):668-672. 14. Kruger E, Voorhees K, Thomas N, et al. Mol Genet Metab Rep. 2022 Aug 10;32:100903. 15. Lindner M, Hoffmann GF, Matern D. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2010;33(5):521-526. 16.Wanders RJ, Ruiter JP, IJLst L, Waterham HR, Houten SM. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2010;33(5):479-494.

STAY INFORMED

Sign up to receive the current disease education information in your inbox.